Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/or/

Relevancy and Engagement

agclassroom.org/or/

Lesson Plan

At Home on the Range (Grades 3-5)

Grade Level

Purpose

Students investigate rangelands by growing their own grass to represent a beef or sheep ranch. Grades 3-5

Estimated Time

Materials Needed

Engage:

- Cow Grazing picture

Activity 1: Trail Blazing

- Jiffy 7 peat pellet pots,* 1 per student

- Plastic cups, 1 per student

- Permanent markers, 1 per group

- Grass seed,* 2–3 teaspoons (10-15 g) per group

- Plastic spoons, 1 per group

- Trail Activity Sheets and Answer Key (laminate the sheets and provide each group with a transparency marker to save paper), 1 per group

- Transparency markers (such as Vis-a-Vis), 1 per group

- Water

*These items are included in the Ranch Starter Kit, which is available for purchase from agclassroom.com.

Activity 2: Grass and Grazing

- Water

- Scissors

Activity 3: Lasso'n Lingo

- Lasso’n Lingo handout

Evaluate

- Computer with internet access for each student

- Ridin' the Range Webquest

- Ridin' the Range Webquest Answer Key

Vocabulary

carrying capacity: the maximum number of animals a piece of land can support without degradation

open range: unfenced areas that can be grazed by livestock

rangeland: large, mostly unimproved section of land that is primarily used for grazing livestock

Background Agricultural Connections

What is Rangeland?

When the term rangeland first came into use in the 1800s, it was used to describe the extensive, unforested lands dominating the western half of North America. Today, rangeland refers to a large, mostly unimproved section of land that is used for livestock grazing. Rangelands can be found in a wide variety of ecosystems, including natural grasslands, savannas, shrublands, deserts, tundras, alpine communities, coastal marshes, and wet meadows. Rangelands are usually mountainous, rocky, or dry areas that aren’t suitable for growing the usual farm crops. However, grass and other plants on rangeland can be used for grazing livestock. People can’t eat grass, but cattle and sheep can turn grass into beef and lamb.

As the human population continues to grow, more space is needed for neighborhoods, businesses, and the cultivation of crops. There are 1.8 billion acres in the United States. This is all the land available for homes, schools, airports, roads, farms, ranches, recreational areas, wildlife habitat, and everything else. Rangelands are important because they provide multiple goods and services and support many uses within the same space; they are multiple-use lands. Rangeland ecosystems provide nutritious forage for grazing livestock, which produce food, fiber, leather, and many other useful by-products. These same rangelands provide forage and habitat to wildlife (including many threatened and endangered species), numerous recreational opportunities, and a unique setting for social and cultural activities. We depend on these goods and services and expect them to be sustained for the benefit of future generations.

In order to use rangelands in all of these ways without damaging them, it is important that rangeland health be closely monitored and managed. So, who owns and manages rangelands? Ranchers may use their own private land to graze their animals or pay a fee to the government to lease public rangeland. Permits are issued by both the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management to allow grazing on public lands. Federal rangeland managers and private livestock owners work cooperatively to ensure that public rangelands are well cared for. Well managed grazing can be both economically and ecologically beneficial. Compared with harvested feeds like corn and wheat, range and pasture provide a relatively inexpensive feed source for livestock. Sales of livestock and other ranching activities contribute to the strength of local economies. Properly managed livestock grazing can also help keep grasslands healthy.

Rangeland management begins with grass. We tend to take grass for granted because there seems to be so much of it. In fact, there is a lot of grass. It is one of our most important and available renewable resources. Grass plays a number of environmentally important roles. Grass covers the soil and holds it in place, slowing runoff of rain, preventing erosion, and reducing the potential for floods. Grass traps and filters sediments and nutrients from runoff, and helps water percolate through the soil and back into streams and ground water.

Cattle and sheep are like rangeland lawn mowers that can help care for grassland ecosystems. Imagine what your lawn would look like if you didn’t mow it! At first glance, when we see animals grazing, it seems like the animal wins all. However, there are more winners here than first meets the eye. The moment grass is shorn, it seeks to restore a balance between its roots and leaves. When the tops of the grass leaves are eaten by grazing livestock, the same amount of root is lost. When the roots die, the soil’s population of bacteria, fungi, and earthworms gets to work breaking down the dying roots. This creates fertile organic matter that enriches the soil.

Rich soils, in turn, support more grass growth. Grasses regrow from the bottom up. Because their growing point is low to the ground, grasses can usually recover well after grazing. However, repeated, heavy grazing can kill grass. When a grass plant is grazed very low to the ground, a large portion of its roots die, and it has little leaf area left to make energy through photosynthesis. Because the plant can’t generate much energy, it takes a long time for the roots to regrow, and the plant is very susceptible to drought. Proper management of grazing involves moving livestock to a new area before grasses are grazed too low and allowing grasses a period of rest to regrow leaves and roots before grazing them again. With proper management, grazing can be a tool for keeping rangelands healthy.

In well-managed grasslands, decaying roots are the biggest source of new organic matter, and grazing animals actually build new soil from the bottom up. In the absence of grazers, the soil-building process would be nowhere near as swift or productive. Grazing cattle aerate the soil with their hooves, scatter seeds, and trim wild grasses. Wildfires have a harder time taking hold on shorter, cropped grass than on longer vegetation. Properly grazed or “mowed” grass can help create healthy green grass!

Utah Rangelands

Rangelands cover about 80 percent of Utah’s land—from desert canyons to rolling hills of sagebrush and juniper to spectacular mountains dotted with lakes and streams. With this kind of land resource, it is important for Utahns to be familiar with rangeland geography, use, health, and management. Because shrub and grasslands cover most of Utah, managed grazing is an important tool for keeping Utah’s lands healthy.

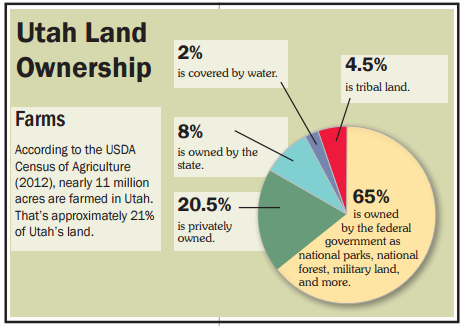

So, who owns and manages Utah’s rangelands? The pie chart shows land ownership in Utah. Most of Utah’s land is publicly owned, and about one-fifth is privately owned. As in many other western states, ranchers may use their own private land to graze their animals or pay a fee to the government to lease public rangeland. When leasing public land, ranchers work cooperatively with federal rangeland managers to ensure that public rangelands are well cared for.

Engage

- Show your students the Cow Grazing picture. Ask your students if they see anything in the picture that looks tasty to eat.

- Explain to the students that humans do not have an adequate digestive system to obtain sufficient nutrients from grasses and other similar plants. However, cattle and sheep thrive by grazing rangelands. In this lesson, students will learn how grazing can be managed to be a benefit to ranchers and to improve and maintain the health of the land.

Explore and Explain

Activity 1: Trail Blazing

- Review with your students the background information concerning rangelands, grazing, and the nature of grass.

- Divide your class into 6 groups. Each group will be taking a different “trail,” and on their way, they will start their own “ranch” with a small planting of grass. Note: Some of the "Trail" activity sheets will be most pertinent to Utah students, but the majority are generic and will be pertinent to students in any state.

- Provide each student with a peat pellet and a plastic cup to hold it.

- Provide each group with a permanent marker, 2–3 teaspoons (10-15 g) of grass seed in a small bowl, a plastic spoon, one of the Trail activity sheets, and a transparency marker.

- Ask students to place the peat pellet into the cup. Explain that you will be pouring a 1/2 cup (120 mL) of water into each person’s cup while each group reads their Trail activity sheet, completes the activity, and then starts their ranch (plants their grass seed) by following the instructions in the sidebar of the Trail activity sheet.

- Instruct the students to begin working on the activity but to also observe their peat pellets. When they finish the activity, the water should be absorbed and the peat pellet completely hydrated. It takes about 15 minutes for the peat pellet to hydrate and expand into a pot in which seeds can be planted.

- When each group has completed their activity and all students have planted their grass seed, ask each group to share what they learned on their trail.

Activity 2: Grass and Grazing

Once the seeds germinate, keep the peat pots moist, and allow the grass to grow until it has reached 2–3 inches (5-7 cm) in height. Students will be applying two different grazing treatments and will leave some of the grass untreated.

Once the seeds germinate, keep the peat pots moist, and allow the grass to grow until it has reached 2–3 inches (5-7 cm) in height. Students will be applying two different grazing treatments and will leave some of the grass untreated.- When the grass is 2–3 inches (5-7 cm) tall, ask the students to use scissors to cut half of the grass blades short—1 inch (2.5 cm)—above the soil to simulate a cow grazing.

- They should clip another quarter of the grass down to the crown—where the blades meet the roots; this part of the blade is white in color. To simulate overgrazing, ask students to clip this quarter area to the crown every couple of days.

- The last quarter section of the grass should remain unclipped.

- Observe the grass for a few weeks, and then make comparisons. What are the results of the overgrazed, grazed, and ungrazed grasses? Ask students how their grazing experiment compares to mowing their grass.

Activity 3: Lasso’n Lingo

- Learning western land terms is a fun way to cement what students have learned about rangelands. Share the following vocabulary list Lasso’n Lingo with students. Discuss the meanings of the words.

- Ask students to write a story using at least 12 words from the list.

- When all of the students have finished writing their stories, ask for volunteers to share what they’ve written with the class.

Elaborate

- Play the My American Farm interactive game The Steaks are High.

- Look up how many acres of rangeland your state has available. Is there a correlation between available rangeland and the quantity of livestock produced in your state? Use the Interactive Map Project website to identify the number of beef cows and sheep produced in your state. Beef cattle and sheep are the livestock species that are most commonly grazed on rangelands.

Evaluate

- Review the concepts discussed in the Trail activity sheets by having students complete the Ridin' the Range Webquest.

- In order to complete this activity, students will need a computer with internet access, the link to the webquest, and an email to send the finished webquest to (provide them your email if you would like to receive their finished work).

- Within the webquest, students will be directed to the following websites to find answers to the questions:

After conducting these activities, review and summarize the following key concepts:

- Rangelands can be public or private land. They are located in open spaces where there is grass and other grazing beneficial to livestock.

- Rangelands are generally not ideal for crop farming due to a variety of factors which can include rugged topography, limited water resources, etc.

- Rangelands are defined in part by their physical geography. Physical geography affects what plants and animals live in an area as well as what kinds of activities humans undertake in an area.

- Grazing rangelands can be beneficial to the environment if it is managed properly.

Acknowledgements

Story-writing activity (Activity 3) contributed by Hooper Elementary (Hooper, UT) teacher Sharlie Wade.

Recommended Companion Resources

- America's Heartland: Riding the Range on a Utah Cattle Drive

- America's Heartland: Wild & Wooly Roundup

- Beef Ag Mag

- Chew It Twice Poster

- Google Earth on the Range Repeat Photographs

- Illustrated Accounts of Moments in Agricultural History

- Levi's Lost Calf

- Little Joe

- NMSU Field Trip: Beef

- Ranch Starter Kit

- Sheep – Utah's Agricultural Cornerstone

- Sheepology: The Ultimate Encyclopedia

- The Steaks Are High Online Game

- Thunder Rose

- Tootsie Roll Conversation About Conservation Terms

- Utah Beefscapes